analysis Asia

5 insights from Sabah election results, including implications for Malaysia politics and PM Anwar

What do the state election results mean for Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim, whose Pakatan Harapan coalition claimed only a single seat out of 22 contested?

Malaysia Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim (right), who is also chairman of the Pakatan Harapan coalition, leaving with Gabungan Rakyat Sabah chairman Hajiji Noor in a vehicle after a campaign in Sulaman, Sabah on Nov 27, 2025. (Photo: ┬ķČ╣/Fadza Ishak)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

KOTA KINABALU: Sabahans woke up on Sunday (Nov 30) to a new state government led by a familiar face.

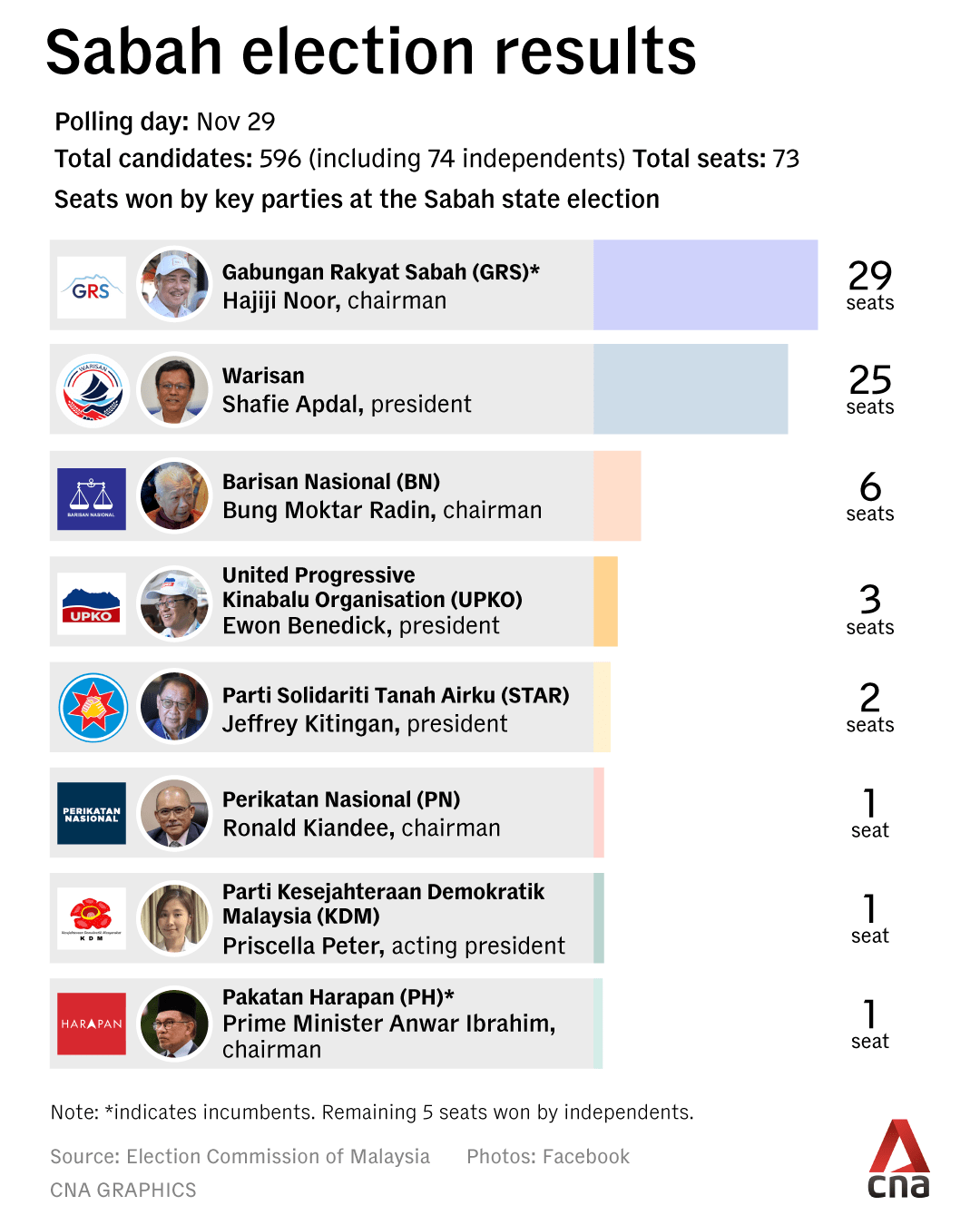

According to official results from SaturdayŌĆÖs polling, the incumbent Gabungan Rakyat Sabah (GRS) coalition emerged with the largest number of seats, allowing its chairman Hajiji Noor to be sworn in as the stateŌĆÖs chief minister for a second term.

But key questions remain. With GRSŌĆÖ 29 seats unable to secure a simple majority in SabahŌĆÖs 73-seat legislative assembly, who will join them to form a coalition government?

And what do the election results mean for Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim, whose Pakatan Harapan (PH) coalition claimed only a single seat out of 22 contested?

While PH looks set to be part of the state government given their electoral pact with GRS, the results have delivered a damning verdict for peninsula-based coalitions like AnwarŌĆÖs, analysts told ┬ķČ╣.

ŌĆ£It's very clear that Anwar has to think carefully about a new set of federal-state relationships, specifically for Sabah and Sarawak,ŌĆØ said James Chin, an Asian studies professor at the University of Tasmania.

In neighbouring Sarawak, the exclusively local party-based Gabungan Parti Sarawak (GPS) commands a stranglehold in the state assembly, putting the state government in a position of strength when negotiating with Putrajaya for more rights, including in crucial matters like education autonomy as well as oil and gas revenue.

ŌĆ£Anwar has to tread carefully, because if he reads the wrong signal from the electorate, he's going to create a lot of turbulence in terms of Sabah and Sarawak politics in the federation,ŌĆØ Chin added.

Here are five key takeaways from the outcome of the 17th Sabah state election:

1. WHO TRIUMPHED, WHO FLOPPED?

First, the losers.

The Democratic Action Party (DAP) - a PH component party - lost all the constituencies it previously held to Warisan.

ŌĆ£Many Chinese voters shifted their support to Warisan instead of DAP, largely due to the perceived lack of integrity at the federal level and corruption scandals involving political elites in Sabah,ŌĆØ said Arvin Tajari, a senior lecturer from Universiti Teknologi MARA (UiTM) Sabah.

ŌĆ£These issues damaged PHŌĆÖs image, especially among Chinese voters.ŌĆØ

DAP, considered popular in several Chinese-majority urban seats, lost all eight seats it contested this time round, despite winning six out of seven at the previous state election in 2020.

AnwarŌĆÖs own Parti Keadilan Rakyat (PKR) also won only one of the 12 seats it contested this year, down from the two out of seven in 2020.

Vilashini Somiah, a senior lecturer at Universiti Malaya, believes PH and DAP ŌĆ£misread the political temperatureŌĆØ in Sabah.

ŌĆ£They assumed Chinese-majority seats would remain safe and underestimated the depth of the ŌĆśSabah for SabahansŌĆÖ sentiment that has been building for years,ŌĆØ she said.

DAP, through its relative silence on the issue of SabahŌĆÖs 40 per cent entitlement to its federal revenue contributions, continued to behave as though its Chinese vote bloc was assured even as ground sentiment showed they were shifting to Warisan, she said.

Sabah has for years been trying to negotiate a return of its entitlement as stated in the Federal Constitution, an issue that has dominated the hustings.

Vilashini also cited negative reaction to the arrest of Albert Tei, the businessman at the heart of an alleged mining corruption scandal implicating GRS-PH, by enforcement agencies under AnwarŌĆÖs government.

ŌĆ£PH and DAP didnŌĆÖt just lose votes. If I am frank, they lost trust and, in Sabah, that carries a long memory,ŌĆØ she added.

Next, the winners.

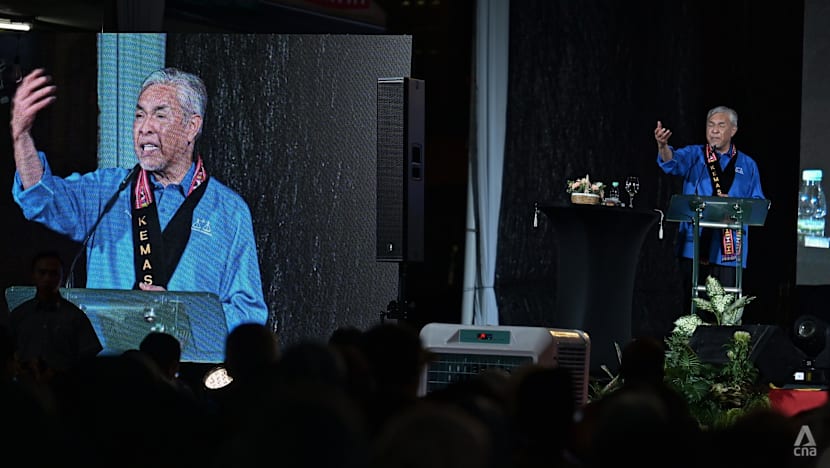

During the hustings, GRS and bitter rival Warisan - led by Shafie Apdal - emerged as frontrunners, with both parties seemingly confident of clinching a simple majority.

They criticised each otherŌĆÖs track records on development in Sabah.

Hajiji consistently attacked municipal waste problems in ShafieŌĆÖs long-held Semporna federal seat, while Shafie maintained that GRS was embroiled in corruption, alluding to the alleged mining scandal.

GRS eventually won 29 of the 55 seats it contested, while Warisan claimed 25 of the 73 seats it fought in.

Going by the number of votes in seats they won, however, GRS won a mere 0.15 per cent more votes than Warisan, an official tally by news agency Bernama showed.

ŌĆ£The best answer I can give is that money politics in the rural areas plays a very heavy role. And Warisan was not able to catch up,ŌĆØ Chin said.

ŌĆ£So Warisan, I think, was really a victim of money politics. But of course, this has been going on in Sabah for a very long time.ŌĆØ

Shafie echoed the same sentiment at a press conference on Sunday afternoon, saying the ŌĆ£use of money was very rampant and clearŌĆØ.

Shafie on Sunday slammed what he described as the extensive use of government machinery and alleged vote-buying during the campaign, without naming any specific party.

Still, Warisan increased its seats from the 23 it won in 2020, showing that the party remained relevant, especially on SabahŌĆÖs east coast, noted Universiti Malaya professor Awang Azman Awang Pawi.

ŌĆ£But it could not overcome the structural advantage of GRS, BN (Barisan Nasional) and PH in machinery, logistics, and the image of stability,ŌĆØ he said.

2. WHO WILL FORM THE NEXT STATE GOVERNMENT?

Awang Azman said GRS and PH will form the ŌĆ£coreŌĆØ of the new government with their 30 seats.

The United Progressive Kinabalu Organisation (UPKO), a former PH component party that won three seats, will ŌĆ£almost certainlyŌĆØ back GRS-PH given that it is traditionally pro-PH and pro-federal government, he said.

The five independents who won could also join the government as they preferred ŌĆ£supporting GRS for stability and political survivalŌĆØ, Awang Azman said.

These 38 seats would give the government a slim majority in the state assembly, noted Adib Zalkapli of geopolitical consultancy Viewfinder Global Affairs.

ŌĆ£A two-seat majority government is still a majority government. The anti-hopping law helps in ensuring stability,ŌĆØ he said.

But Chin said GRS would look to rope other parties in given the importance of a more stable two-thirds majority in MalaysiaŌĆÖs volatile politics.

Another possible partner is Barisan Nasional (BN), with six seats, although Chin said this was ŌĆ£highly unlikelyŌĆØ given the ŌĆ£animosityŌĆØ between Hajiji and Sabah BN chairman Bung Moktar Radin. The latter had previously tried but failed to topple HajijiŌĆÖs government.

ŌĆ£But anything is possible. The big question now in Kota Kinabalu is whether Warisan can cut a deal with Hajiji,ŌĆØ Chin said.

3. WHAT ISSUES DID THE ELECTION RESULTS SURFACE?

The vote swing towards Sabah-based parties like GRS and Warisan indicated that a ŌĆ£local vs national partyŌĆØ sentiment, which had dominated the hustings, prevailed, Chin said.

Some netizens pushed the narrative that a Sabah government fully composed of local parties could better push Putrajaya for the stateŌĆÖs full and rightful claims under the Malaysia Agreement 1963 (MA63).

MA63, the legal instrument signed in 1963 as the basis of the formation of the Federation of Malaysia, recognises Sabah and Sarawak not as mere states but as equal partners with West Malaysia.

ŌĆ£If this pattern continues, regional politics in East Malaysia will strengthen further, similar to developments in Sarawak. This will likely result in continued decline in support for national coalitions in Sabah and Sarawak,ŌĆØ Arvin said.

The national BN coalition was not spared either. For this yearŌĆÖs election, BN had formed a separate pact with fellow national coalition PH to mirror their partnership at the federal level.

BN ended up winning six of the 45 seats it contested, down from the 14 it won in 2020.

ŌĆ£This shows that BN has not fully recovered since the (federal) electoral defeat in 2018,ŌĆØ Adib said.

The analyst was referring to how the once-dominant ruling coalition was toppled for the first time after 61 years at the 2018 General Election, following the massive 1Malaysia Development Berhad corruption scandal.

Sabah BN chief Bung Moktar scraped through in his Lamag seat with a mere 153 vote majority, while fellow party warlord Salleh Said Keruak lost his Usukan seat to a Warisan candidate by 442 votes, Adib noted.

ŌĆ£This shows that there is some kind of renewal in Sabah politics,ŌĆØ he said, also pointing to defeats for long-time Sabah politicians Anifah Aman and Pandikar Amin Mulia, a former federal minister and a former parliament speaker, respectively.

UMŌĆÖs Vilashini said Sabah voters have demonstrated that loyalty cannot be assumed and outcomes cannot be predicted.

ŌĆ£The Bung Moktar constituency, and even several of WarisanŌĆÖs traditional strongholds, illustrates this clearly: Tight margins, unpredictable swings, and no longer any guaranteed base,ŌĆØ she added.

ŌĆ£Putrajaya must now recognise that SabahŌĆÖs autonomy demands carry real electoral weight. SabahŌĆÖs agency has evolved beyond nostalgic gratitude politics. Voters are sophisticated, strategic and willing to punish complacency.ŌĆØ

4. WHAT DO THE RESULTS MEAN FOR ANWAR?

UiTMŌĆÖs Arvin called the election results a ŌĆ£major setbackŌĆØ for Anwar, and said his daughter Nurul IzzahŌĆÖs appointment as election director was widely perceived as unsuccessful.

ŌĆ£For Nurul Izzah, who was recently appointed deputy president of PKR, the outcome may damage her political credibility,ŌĆØ he said.

ŌĆ£Several party decisions, such as contesting in Merotai, were heavily criticised and seen as strategic miscalculations.ŌĆØ

Nurul Izzah, in a joint statement with PKR secretary-general Saifuddin Nasution Ismail, said she took ŌĆ£full collective responsibility as part of a team for this outcomeŌĆØ.

Anwar said in a social media post the federal government "fully respects the strong and clear message" of the state's voters as he congratulated Hajiji on his reappointment.

"They are demanding real change after being faced with injustice and neglect by almost all parties," Anwar wrote. He did not touch on PKRŌĆÖs performance.

Vilashini said the election results delivered ŌĆ£both comfort and cautionŌĆØ for Anwar.

ŌĆ£On one hand, GRSŌĆÖs return - backed by UPKO, PH and five independents - signals that Sabah is still extending an olive branch to the Madani government,ŌĆØ she said.

ŌĆ£But the message from Sabahans is unmistakable: They do not want a state government visibly tethered to political forces in Malaya (West Malaysia).ŌĆØ

Vilashini said AnwarŌĆÖs government would need to approach Sabah with a ŌĆ£far lighter touchŌĆØ moving forward, noting that the premier's vulnerability lies in perception.

ŌĆ£If Sabah continues to experience stalled development, weak service delivery, or governance failures under a GRS-led administration linked to PH, that frustration will boomerang back to Putrajaya,ŌĆØ she added.

Anwar should focus more deeply on national development and reduce political rhetoric, as many voters perceive his leadership as overly focused on political narratives rather than concrete reforms, Arvin said.

ŌĆ£In Sabah, attention will now turn to whether the federal government fulfils its commitment to the 40 per cent revenue entitlement promised under MA63,ŌĆØ he added.

ŌĆ£Delivering this would significantly improve the credibility of the federal administration in East Malaysia.ŌĆØ

The Sabah polls produced the ŌĆ£best election outcomeŌĆØ for Anwar as he would have an ŌĆ£easier timeŌĆØ negotiating the 40 per cent issue with Hajiji, said Chin from the University of Tasmania.

An ŌĆ£indirect implicationŌĆØ for the Anwar, however, is that GRS has now won a ŌĆ£strong mandateŌĆØ on its own, compared to its victory in 2020, Chin said.

When GRS won in 2020, the coalition still comprised BN lynchpin party the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) and Parti Pribumi Bersatu Malaysia, whose leader Muhyiddin Yassin was prime minister at the time.

ŌĆ£GRS will probably push Anwar to give them one more federal deputy ministerŌĆÖs post in the upcoming capital reshuffle,ŌĆØ Chin predicted.

5. WHAT TO EXPECT FOR THE NEXT GENERAL ELECTION?

The Sabah election was a ŌĆ£stress testŌĆØ of the strength of the Anwar government brand beyond peninsular Malaysia, as well as stability of large coalitions like PH, BN and GRS, which are all part of the AnwarŌĆÖs unity government at the federal level, UMŌĆÖs Awang Azman said.

ŌĆ£If SabahŌĆÖs lessons are ignored, political undercurrent in other states could grow ahead of GE16,ŌĆØ he said, referring to MalaysiaŌĆÖs next general election, which must be held by February 2028.

Adib, from Viewfinder Global Affairs, said PH and GRS are likely to form a ŌĆ£more cohesive partnershipŌĆØ in federal elections.

AnwarŌĆÖs dependence on Borneo parties like GRS will prove even more crucial in helping PH secure a parliamentary majority in federal elections, said Asrul Hadi Abdullah Sani, a partner at strategic advisory firm ADA Southeast Asia.

ŌĆ£With Bornean sentiment hardening against Putrajaya, Anwar faces the real possibility of PH performing poorly in Sabah and Sarawak, narrowing his coalitionŌĆÖs path to 112 seats and increasing the risk of a hung parliament,ŌĆØ he said, referring to the number of seats needed for a simple majority in the 222-seat federal parliament.

ŌĆ£A weaker showing in East Malaysia would empower blocs like GRS and GPS as key kingmakers, meaning Anwar must start preparing for post-GE bargaining and begin negotiations on autonomy, development funding and MA63.

ŌĆ£It would also make strengthening cooperation with UMNO in the Malay-belt states essential for him to form the next federal government.ŌĆØ