Commentary: Southeast Asia canāt afford to sit out the ākiller robotsā debate

How lethal autonomous weapon systems are defined could determine whether existing weapons will be regulated or prohibited, says Liu Mei Ching from the S Rajaratnam School of International Studies.

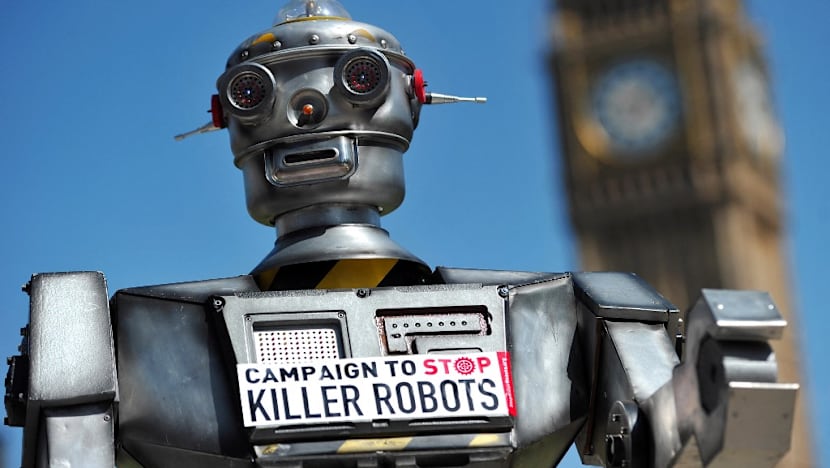

A mock "killer robot" is pictured as part of the Campaign to Stop "Killer Robots," which calls for the ban of lethal robot weapons that would be able to select and attack targets without any human intervention. (Photo: AFP Photo/Carl Court)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SINGAPORE: Think super-intelligent killer robots and our minds flash to popular films and television series like The Terminator and Black Mirror.

While the idea of these sci-fi versions running rampant remains far-fetched, lethal autonomous weapon systems (LAWS) have nonetheless raised concerns ā from the risk of losing human control during conflict to the challenges in ensuring accountability and compliance with international law.

Due to myriad humanitarian, security and legal concerns, the United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres has urged the international community to adopt a legally binding instrument for these weapon systems by 2026. This discussion started in 2013 and is currently led by a UN Group of Governmental Experts (GGE) that recently convened in September.

Existing weapon systems may already fit the working definition of LAWS. As of May, the GGE defines them as āan integrated combination of one or more weapons and technological components, that can select and engage a target, without intervention by a human user in the execution of these tasksā.

Air defence systems at military bases that are designed to autonomously strike incoming missiles, rockets or mortars could qualify. The most prominent example is the Iron Dome in Israel. Other planned systems that might mirror its technology include the United Statesā Golden Dome, or Taiwanās T-Dome which was announced in October.

While there are no such air defence systems in Southeast Asia, how LAWS are defined could determine whether weapons already in Southeast Asian statesā arsenals will be included.

SOUTHEAST ASIAāS VOICE IN WEAPONS DISCUSSION

The potential regulation or prohibition of existing weapon systems underscores the importance of Southeast Asian states joining and shaping the LAWS debate.

Close-in weapon systems (CIWS) used on ships, such as the Palma CIWS on Vietnamese frigates, could also qualify. LAWSā definition could also include active protection systems designed to protect military tanks against incoming missiles.

Loitering munitions (also commonly called kamikaze drones), which Indonesia and Malaysia have taken an interest in, could also be included.

Sitting out of the conversation means letting others define the rules, including countries that are major weapons manufacturers.

UNCLEAR POSITIONS AND CONCERNS

But the positions and specific concerns across Southeast Asian countries are still unclear.

Four ā Cambodia, Laos, the Philippines and Singapore ā have ratified or acceded to the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW), making them a High Contracting Party. This grants them the full right to participation, including the right to vote in the GGEās decision-making, as compared to observers who do not have. Vietnam is a signatory but has not yet ratified the convention.

Among them, the Philippines and Singapore are the most active participants.

The Philippines has been engaged in the LAWS debate since the GGEās inception. Its commitment is highlighted by its nomination as a Friend of the Chair, a role that involves facilitating consultations and helping the GGE chairperson build consensus.

The Philippines supports a legally binding instrument on LAWS. However, it did not support a joint statement delivered by Brazil in September which called for the negotiation of such an instrument. This could be due to a number of reasons, such as the language of the statement or process constraints, as representatives might have insufficient time to consult their capitals.

Singapore acceded to the CCW in 2023, and its interventions during the GGE meetings have received praise from other states, such as Austria, for being pragmatic, bringing real-life examples, and setting an example for others to follow.

Singapore supported, not the joint statement delivered by Brazil, but another statement with Australia, the United Kingdom, Canada and others, on considering the next steps but which stopped short of calling for negotiations.

Without delving into the technical details, if states ultimately decide to pursue a legally binding instrument, it could be established as a new protocol under the CCW. If states decide against a legally binding instrument, non-legally binding measures, such as a political declaration, may help to shape norms of behaviour and lay the foundation for a future legally binding instrument.

HOW TO ENGAGE IN THE LAWS DEBATE

It is essential that more Southeast Asian states engage in the LAWS debate.

Southeast Asian states could ratify or accede to the CCW to become a High Contracting Party, though the process is lengthy and typically requires a state to enact legislation. Alternatively, they could consider joining as observer states.

Observer Thailand did not actively intervene during the September meeting, but it joined other states in calling for the negotiation of an instrument for LAWS. This support came amid its recent border conflict with Cambodia ā a conflict in which armed drones were used to inflict damage.

Drone technology is generally regarded as the precursor of LAWS because the foundational technologies, such as sensors, navigation and robotics, that support drones are essential for developing LAWS. For a Southeast Asian nation recently involved in a conflict featuring drones, Thailandās action underscores the concerns raised by increasingly autonomous weapons.

The issues of LAWS that are currently being discussed at the GGE are closely linked to the interests of Southeast Asian states. More should make their voices heard.

Mei Ching Liu is an Associate Research Fellow with the Military Transformations Programme at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Singapore.