analysis East Asia

China-Japan diplomatic row: What’s driving Beijing’s anger - and why this time is different

From China’s point of view, the Japanese Prime Minister’s remarks on Taiwan test a red line - a trigger that sets this dispute apart from past flare-ups, analysts say.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

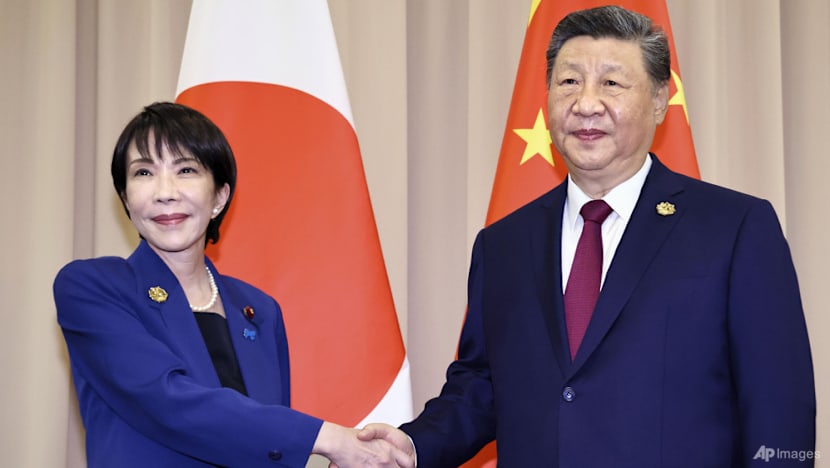

BEIJING: China’s sharp pushback against Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi’s comments on Taiwan may point to deeper concerns, analysts say, in a reaction that goes beyond routine diplomatic theatre.

They believe Beijing views the remarks not as an off-hand comment but as testing a “red line” over Taiwan and advancing what it sees as a “dangerous” effort to “normalise” Japan’s military by eroding post‑war restraints - a trigger that sets this dispute apart from past flare-ups over wartime history or the disputed Senkaku/Diaoyu islands.

Speaking to lawmakers on Nov 7, Takaichi said: “The so-called Taiwan contingency has become so serious that we have to anticipate a worst-case scenario.”

She added that a Chinese attack on Taiwan could trigger the deployment of Japan’s Self-Defense Forces (JSDF) if the conflict posed an existential threat to Japan, whose territory lies just 110 kilometres from Taiwan.

“This is not a one-off gaffe or a case of inexperience - it is targeted,” said Wang Yiwei, director of the Institute of International Affairs at Renmin University of China.

“Treating it (Taiwan) as a country and openly talking about military intervention … there's no question that this is a substantive escalation,” he added.

Beijing rejects any external interference on Taiwan, which it regards as a domestic matter and a core national interest. It claims sovereignty over the self-ruled island and insists it must ultimately come under its control - and has not renounced the use of force.

Wang described Takaichi’s remarks as “part of a broader, dangerous trend” toward constitutional revision, a clearer security linkage to Taiwan, and growing efforts to frame the issue as an “existential crisis” for Japan.

Her use of the term “existential crisis” is “the same excuse Japan used to justify launching aggression in World War II,” Wang said.

“And this year marks the 80th anniversary of the victory in that war. To say something like this - it’s the wrong statement, at the wrong time, in the wrong place,” he added.

Writing in a commentary piece published on the Weibo microblogging site, Shen Yi, a professor at Fudan University’s School of International Relations and Public Affairs, said Takaichi’s words fit into what he called a “systemic” effort to shed pacifist constraints.

“Sanae Takaichi’s remarks are, in essence, an act of summoning the spirit of Japanese militarism,” Shen said, adding that the risks include reviving militarist narratives and legitimising JSDF roles in forward scenarios.

“China’s task, therefore, is to deter, correct, and ultimately eliminate such words and actions from Japan,” he said.

BREACHING A SENSITIVE RED LINE

It’s a sensitive topic at a sensitive time, experts said. In a year when Beijing marked the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II, linking a “Taiwan contingency” to Japan’s collective self-defence could, in China’s view, be seen as a step over the line.

Lim Tai Wei, East Asia observer at Soka University in Tokyo, told Â鶹 that by explicitly tying a Taiwan contingency to the legal basis for collective self-defence, Tokyo is deemed as “publicly testing the tolerance level Beijing has tried to keep implicit”.

Japan’s 2015 security legislation - which allows the country to come to the aid of an ally in a conflict deemed an existential threat - had already expanded room for the JSDF, he said. What's new now, he added, is the clarity of the Taiwan linkage.

“Sino-Japan ties have been a cyclical one, the current (episode) marks the downturn of this cycle.”

Taiwan was a Japanese colony from 1895 to 1945 - ceded by Qing China after the Treaty of Shimonoseki and placed under Chinese administration after Japan’s WWII surrender - a legacy that still shapes Beijing-Tokyo-Taipei relations.

Renmin University's Wang said the stakes feel higher because Taiwan is framed in Beijing as a core interest that’s non-negotiable.

“Once a sitting Japanese leader hard-codes Taiwan into the logic of collective self-defence, the precedent matters more than the sentence,” Wang said.

“(Takaichi) is not inexperienced. What she said is representative. Her approval rating is so high, right? So this reflects (the sentiment) of Japan’s right wing.”

“The situation has become very serious. And she not only refuses to retract her remarks, she (also) won’t apologise.”

Building on that assessment, Shen from Fudan University widens the frame from immediate signalling to a longer game.

In his view, even a tactical climbdown in Tokyo wouldn’t resolve what Beijing regards as the structural problem - the steady mainstreaming of ideas that loosen post-war constraints and normalise JSDF roles around Taiwan.

“Even if Japan were to retract Takaichi’s remarks or force her resignation, that would be only a temporary success, not the final goal,” he said.

The deeper concern, he noted, is historical and societal.

“The persistence of militarist sentiment in Japan is deeply entwined with its political, economic, and cultural ecology - and more profoundly, rooted in its collective history and national culture,” Shen added.

Responding to reports that Japanese officials plan to change JSDF rank titles and revive prewar terms such as “taisa” (senior officer), Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Mao Ning said during a news conference on Nov 18 that Japan’s right-wing forces are “breaking free of the pacifist constitution and going ever further down the path of military expansion”.

“We will never allow the revival of Japanese militarism or any challenge to the post-war international order,” she said in comments carried in a Xinhua report.

Against that backdrop, China’s “Victory Day” commemorations this year carried added weight.

On Sep 3, the People’s Liberation Army staged a grand 80th-anniversary parade in Beijing showcasing advanced kit - from hypersonic and intercontinental missiles to stealth aircraft and underwater drones - with Chinese President Xi Jinping using the moment to stress sovereignty and historical memory as guideposts for present policy.

And that show of strength fed straight into Japan’s security debate, experts said.

On Nov 7, Japanese Defence Minister Shinjiro Koizumi called for an open debate on adopting nuclear-powered submarines - a once-taboo topic - while Takaichi’s new government has moved to broaden defence exports after Komeito’s exit from the ruling coalition.

To Beijing, these steps point to structural change rather than a rhetorical blip, observers asserted.

The shift is also visible in how Japan treats its long-standing “three non-nuclear principles”, which once barred possession, manufacture and stationing of nuclear weapons or related platforms, noted Wang.

Now, he argued, Tokyo is “inviting them in” - a move aimed at “drawing the US even closer,” and, if necessary, accelerating its own militarisation.

"(Japan) looks tough on the surface, but underneath there’s domestic and international anxiety. And since China’s Sep 3 military parade, China’s strength, combined with its push for national reunification, has created this kind of dual anxiety in Japan," said Wang.

MEASURED RESPONSE BY CHINA - FOR NOW

China has escalated its response on multiple fronts.

On Thursday, its foreign ministry summoned Japan’s ambassador to warn against any interference in Taiwan.

By Friday night, China had expanded its pushback beyond diplomacy - issuing a travel advisory that targeted Japan’s tourism sector. About 7.5 million Chinese tourists visited Japan in the first nine months of this year, the largest number from any country and about one-fourth of the total.

China’s education ministry followed up with a warning to students on Sunday about recent crimes against Chinese in Japan, though it didn’t advise them not to go.

At sea, China has paired rhetoric with presence: Coast Guard patrols around the Diaoyu or Senkaku Islands and pre-announced PLA live-fire drills - actions calibrated to show resolve while staying below the threshold of direct confrontation.

Beijing’s response so far, Wang said, is about deterrence - not theatrics.

“It’s not just for domestic purposes - it’s mainly about (warning) Tokyo,” he said, adding that if Beijing fails to react early, “(Japan) will keep pushing further.”

He said Beijing was also watching “how the US responds - will Washington rein in its so-called allies?”

Fudan University’s Shen describes current Sino-US ties as “a long game”.

China is responding from a position of growing capability and intends to use a full toolkit, he said in his Weibo commentary.

“From public and diplomatic condemnation to economic sanctions, and when necessary, the precise use of military force” - sequenced and scaled over time.

The process “cannot be achieved overnight”, he cautioned, and is designed to correct and deter rather than to trigger a break.

This week, Japan’s embassy in China put out a cautionary travel advisory - warning citizens to exercise caution, travel in groups and avoid crowded places amid the deteriorating dispute.

The chill has also extended to cultural exchanges. Chinese distributors suspended the releases of at least two Japanese anime films.

Crayon Shin-chan the Movie: Super Hot! Scorching Kasukabe Dancers and Cells at Work! will not be shown in China, state broadcaster CCTV said in a report, calling it a “prudent decision” that reflected souring audience sentiment.

“THINGS WILL KEEP GETTING WORSE”

Before this flare-up, Beijing and Tokyo had been edging back towards pragmatism.

On Jun 29, China announced a partial lift of its ban on Japanese seafood, resuming imports from approved regions while keeping restrictions on 10 prefectures including Fukushima.

Both governments also revived economic dialogue. On Mar 22, foreign ministers co-chaired the sixth China-Japan High-Level Economic Dialogue in Tokyo and announced 20 areas of cooperation, from supply chains to services - a signal that both sides wanted economic ballast even as frictions lingered.

With global trade unsettled by US tariff turbulence in 2025, both Beijing and Tokyo had incentives to keep commerce steady.

China and Japan remain deeply enmeshed trading partners, with two-way flows still large as of late 2025, and both sides mindful of headwinds from great-power competition, noted analysts.

Interdependence also runs through people-to-people ties. For Japan, China remains a major source of visitors and students - a reliance underscored by market jitters after Beijing advised against travel to Japan this week.

Whether the latest saga reverses those gains is the question.

“Of course, we don’t want that. But that’s not how Takaichi and her team see it,” Wang said.

But he added that Washington “doesn’t have the bandwidth or interest to mediate or de-escalate” right now.

His bottom line is stark: “Overall, things will keep getting worse. Any improvement will only be temporary. There’s no doubt the relationship will deteriorate further.”

Lim from Soka University strikes a more conditional note. How long any chill lasts, he said, “is dependent on the efforts of moderating forces on both sides”.

Separation of politics and economics - seikei bunri in Japanese, or zheng jing fen li in Chinese - has historically served as a safety valve, allowing trade and investment to proceed while tempers run hot.

“(In the past) they had been able to separate rhetoric from trade or economic exchanges,” Lim said.

Shen’s read is that the contest will also increasingly play out in the arena of public opinion.

Coordinating domestic and international narratives to magnify pressure is both “a new challenge” and “a new opportunity”, he argued - an iterative process of building institutions and voices able to articulate China’s case as the struggle unfolds.

In practical terms, that points to a rockier equilibrium: more frequent grey-zone friction at sea and in the air, sharper messaging, and selective economic levers - even as embassy doors stay open and trade forums keep meeting, he asserted.

Analysts said misreading remains the hardest variable to manage. Between the two countries’ narratives lies the risk that signals are interpreted as invitations rather than brakes.

Avoiding that outcome, they said, would likely require not only back-channel contact but clearer public messaging about what each side will, and will not do.

It also hinges on assumptions. Experts noted that underestimating the other side is among the quickest paths to escalation.

“Japanese people tend to think China’s military parades and weapons displays are just for show, not battle-tested," Wang said.

“They may think it’s better to take advantage of the current situation before China becomes even stronger (but) in my view, many Japanese, and Americans too, still fundamentally look down on China and don’t understand its real strength today.”